Blog

Rules For Drawing Cartoons

24 Jan 2024A good friend and I were chatting about his job. He was talking about how they were putting in place a number of rules for all the people doing jobs like his. My natural instinct was that this must make it harder to do his job. That people are creating bureaucracy. He went into greater detail, but I really didn't know his industry to know heads from tails. He said that this was a good thing. He compared it to the design rules for cartoons. And it got me thinking.

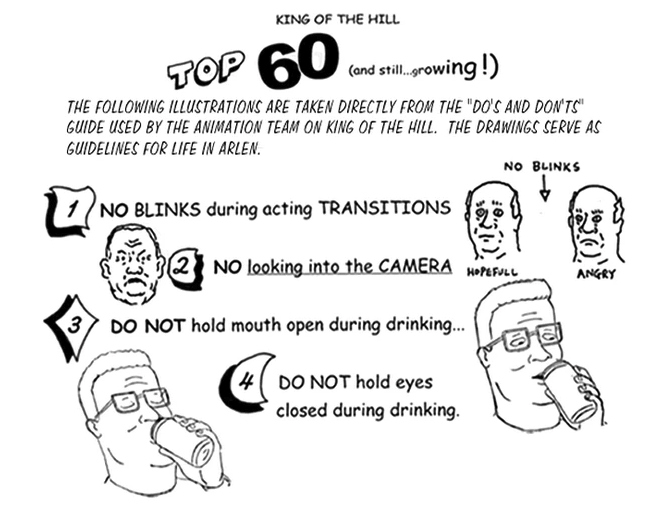

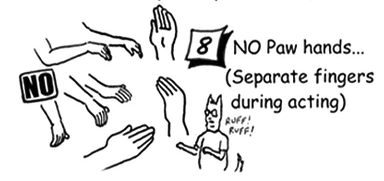

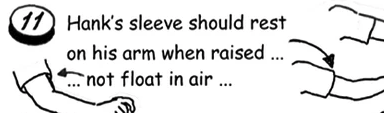

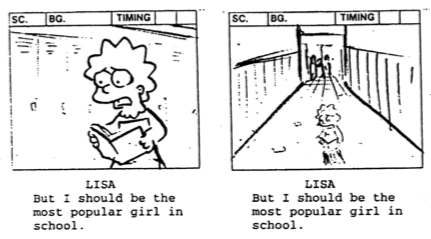

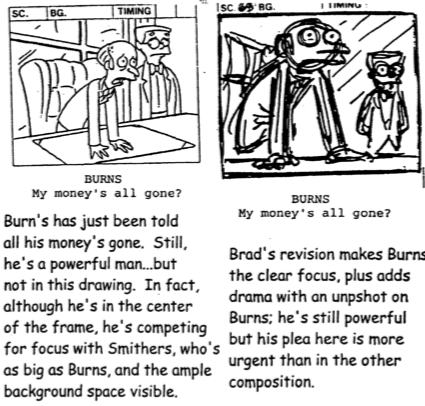

Each cartoon has their own style. It's necessary to establish the brand and for differentiation. Rules communicate to viewers what to expect. And when you break the rules—its for effect. Though there are some rules that you don't break.

In addition to some of the simpler and strict rules like those above. There are guidelines to follow in order create the desired effect. I think about rules like these as if they were a director. The director knows where he wants to put the camera and why. Individual cartoonists may not know how or why to "move the camera."

These artifacts are written down guidelines to make sure everyone is on the same page about how we work together to achieve a cohesive look and story between dozens of different individuals. Everyone has their preferences and opinions. At the end of the day we do all need to work together towards a single destination.

My good friend then asked me:

What are the rules for your company?

I honestly had nothing that I could reasonably point to as an answer for him. As I look around the industry at-large I see "Thought Leaders". Many of them are very vague. The rules we saw for cartoons above are very specific. I really don't think I've ever seen something so specific before. On some level "if the compiler accepts it, it works!" is the bar, even if that bar is incredibly low.

We have to do better. On my very last project I started to do just that. I used ADRs to explain why I was refactoring code to fully utilized class-based views in django-rest-framework. I explained why I was moving code out of views and into serializers. I explained which methods you ought to be overriding to achieve your outcome. And which methods should not be overridden. I even had an example of when I had to break that rule. I wrote a knowledge base entry in our wiki and shared it with the wider dev team.

I received amazing positive feedback on what I was writing up from several people. This is definitely a practice I am going to repeat in the future.

Read more: Rules For Drawing Cartoons

Acting Like an Operator

18 Jan 2024I have been putting together some interesting correlations that I have observed throughout my career. It is giving me a realization about why I care about what I care about. I'm still figuring it all out, and this post is one attempt to vocalize a part of it.

I have noticed a gap in outcomes between software engineers who have had to be operators, and those that have never been operators. When I mean operators—I mean responsible for more than just producing code that goes into production, and if it breaks in the first 48hrs fixing it.

"DevOps" is a convenient label for this, but it's not the whole part. Of course a culture of DevOps (note: this is not a team whose name is DevOps) is a good thing. But that doesn't necessarily make someone an operator that has an interest other than software qua software.

One reason that engineers making products for other engineers works so well is because the ones who are most interested in this are the ones that need tools that don't yet exist. Because they are operating something. This is the best version of dog-fooding, or drinking your own champagne, whichever metaphor you prefer.

I've been an operator when I was a software consultant. My job was building software for my clients to operate. I felt the pain of operators, and it was tied directly to my paycheck. I had immediate access to my users. And if I couldn't solve their pain, they would stop paying me.

I've been an operator of a gym, with some friends. We started a powerlifting and olympic weightlifting gym in a warehouse. Paid rent, got equipment, and tried to get people in the door. It was, and remains very successful.

Growing up our family friends were operators. Construction, plumbers, electricians, roofers, you name it. One of them had a particularly strong influence on my I will never forget. I worked construction renovation with them for a summer.

In my career I have observed that software engineers who don't take on an operators perspective when building tend to have some commonalities. Maintaining their software is difficult. Operating their software is difficult. The concerns of those who are operating it are less important than some technical merits. This often holds back improvements. A perpetual list of things to do is seen a "a good thing" and predictable output is the highest possible good, regardless of whether there is any value in that list. Whenever the mood or task at hand feels Sisyphusean, that is when I know in my gut that the folks building do not have the perspective of an operator.

On the other hand. When the folks building have the perspective of an operator, you see creativity, and a varied approach to solving problems. These folks have more than a hammer, and there are more than just nails in the world. You see defensive designs because they expect the unknown. Problems rarely have a large blast radius. And best of all, the folks who work this way are able to move on from what they've built. They're not tied to it like an anchor. Because the maintenance is low, and its easy to operate. It might still have flaws and lack specific things. But they are able to go off and build the next new thing.

Because they are focused on value there is not an endless list of tings to do. Many things & directions have been ruled out. They don't react to incoming feedback by jumping and saying "How high?" They don't react until there is something with large value enough to return and work on it.

Why is the determining factor "acting like an operator"? Because operators have Important Things To Do. Operating the software is something that has to get done in service of the true task. Operating is never itself the goal. The less time and energy spent operating, the more time and energy you have for value creation.

As the line from Halt and Catch Fire goes "Computers aren't the thing. They're the thing that gets you to the thing."

Read more: Acting Like an Operator

Ownership At Work

18 Dec 2023When we talking about "who owns what" most commonly I hear people discuss it in terms like these:

- "Who owns this module in the codebase?"

- "Who owns this page in the application?"

- "We don't own that!"

The way people talk about ownership betray some of my most important values. This is how I translate that kind of talk; "We don't want to touch it", "It is their responsibility", "I am not allowed". You may not want to touch it, but if its in the way of doing your job, I want to see you activate, not wait around for someone else. It may in fact be someone else's responsibility—that doesn't help us make progress in the moment. Do you mean someone is actually penalizing you when you tried?

I value people who activate, get involved, make decisions, and finish work. Every one of these questions avoids getting involved, looks to someone else to make a decision, and does nothing to finish. Finishing something is the only way to create value, hit your goals, and start working on the next thing.

I don't think people are thinking about the implications of their idea of ownership. Here is just a small bit of the quagmire this creates:

When we talk about ownership do we really mean "only owners can modify it"? Does everything only have one owner? Doesn't that make collaboration really really difficult? What does it mean to possess code? Its not even a real thing in the world! What do we do with a list of things that are not owned? If you're claiming ownership why is no one else allowed to touch it? Why do you need such tight control? What value does that create for you? What value is that denying for others? If someone else owns something, and you need a change, and you're not allowed to do it, you've now linked your success to their ability to make that change on your timeline. Is that really how you want to work?

If you own something, and its not successful, does that mean you ought to be fired? I have rarely met anyone who would agree with that statement, but also still believe in "ownership". After all, what is ownership without fully responsibility for the outcomes?

I would love to change how we talk about ownership. I think talking about it this way causes too much stress and anxiety for teams. I want the engineering teams I work with to think about ownership in these terms:

- I own how I invest my time each day.

- I own making progress on my team's goals.

- I own collaborating with my peers in order to find the best way forward.

Software Engineering is a team activity. No one person can do it all. No one person owns the code. No one person owns the whole outcome of our work. But you absolutely own getting involved, working hard, and the impact you make. No one but you can stop you.

Read more: Ownership At Work

Opinions Held

27 Feb 2023I think the idea of "Strong Opinions, Weakly Held", as it is commonly received, is a terrible concept. Another word for "strong opinion" is "a belief". Beliefs should be required to have costs associated with them. "Weakly held" implies to me that you create beliefs absent any costs.

In my view, beliefs are strongly held. They are created based on impactful lived experiences. These beliefs that I have, have come at great personal cost to me in blood, sweat, and tears. I don't know about others, but I do not take lightly to having my lived experience "weakly held" and brushed aside easily.

Weak opinions, weakly held sounds entirely plausible to me. That sounds like brainstorming or doing some hand-wavey "napkin math. Yes, you better hold those very weakly. You spent as little time as possible coming up with the opinion. When someone else comes along, having done more work, you should probably perk up and listen to what they've got.

We don't want to hold on to our beliefs because they are simply ours. But rather because we know why we believe them, how they got created, and how are they working for us. Does our most recent experience comport with our established beliefs?

Read more: Opinions Held

Humans Acting At Scale

18 Nov 2022The aphorism "A person is smart, but people are stupid" has always stood out to me. It never sat right. If an element of a set contains a property, then the set ought to exhibit the same property. Right?! Well, what are we really trying to communicate when we say this?

I think one aspect of what we're trying to say is that when we take a given person in a situation, we're probably imagining that person at their best. Any given person in their best moment, ready, willing and focused, is going to behave as intelligently as they possibly can.

But what are we saying about "people" in groups? We're no longer imagining one situation, but all situations. And not when any of those given people are at their best, but everywhere along the Bell curve of their possible performance.

We're comparing an individual high water mark, with the average of a bunch of people between their good and bad moments and days. No wonder! I think there is a more charitable description than we can give this than the common aphorism. That is: Humans Acting at Scale.

Why am I interested in this as a software engineer? I build systems that other engineers operate. I build products that users & customers operate. When building these systems and products there are a lot of decisions to make along the way. When we're making these decisions are we thinking about our users and their abilities?

Are we thinking that they will only be operating the system or product after 10 hours of good sleep, after their first cup of caffeine, in their favorite outfit, without a care in the world, and totally focused on doing an excellent job today? Or do we think that they'll be operating the system or product with one hand because with their other hand they are on the phone trying to get someone to come fix their furnace, after they got a bad night's sleep because their dog was up until 1am vomiting? If they drop their phone on the keyboard, or the cat walks across it—what happens?

How many things does this operator need to remember (Knowledge in the Head) versus things the system is showing them and giving them feedback on (Knowledge in the World)? How are details surfaced to the operator? How are expectations and impact of their operations communicated back to them? Do they get a clear confirmation screen? Are their actions reversible?

Once we're working with a product or system that is operated by a group, or multiple groups, of people we have to stop considering the fact that we know one of the individual humans who is operating it. "I know Steve, Steve is great at his job. This is a little complicated, but he can handle it." We have to consider how many other people are also operating it, who no doubt are also good at their job. But that we are all simply human, and our ability to perform & operate varies all the time due to an uncountable number of factors.

Demanding a standard of "just be better and don't make mistakes next time" is not a valid approach you can have towards operators.

Designing with empathy is not about pitying people, or even thinking you're better than them (you're not). It is about designing for the worst outcomes and making sure your system and product support what the humans need in the face of those worst outcomes.

Read more: Humans Acting At Scale